Back in May, an angry constituent asked Congressman Raul Labrador, an Idaho Republican, why he had voted for the House health care bill, which the constituent claimed would cause people to die for lack of Medicaid funding. The Freedom Caucus member shot back with a now infamous retort: “Nobody dies because they don’t have access to health care.”

Amid backlash over what he now describes as an inelegant statement, Labrador tried to clarify his remarks, saying, “I was trying to explain that all hospitals are required by law to treat patients in need of emergency care regardless of their ability to pay and that the Republican plan does not change that.”

But Labrador forgot to mention that although hospitals are required to treat severely ill patients, they are also allowed to bill those patients for that care. That means that people without insurance often find themselves either avoiding emergency rooms altogether or driving long distances to hospitals known for being more forgiving of medical debt. Labrador overlooked the life-threatening risks that financially strapped people take to keep out of medical debt.

Insurance sometimes saves lives by enabling people to get emergency care close to home, without fear of financial insolvency.

This travel-and-die phenomenon is not what most insurance enthusiasts think about when they say insurance improves health. Instead, they talk about how insurance makes people more likely to receive the primary care that prevents life-threatening illnesses – mammograms and colonoscopies, blood pressure pills and flu shots. They point out that patients with insurance are more likely to see doctors when they start developing worrisome symptoms. With insurance, the cost of a cardiology appointment no longer stands in the way of getting that “heartburn” checked out. In short, insurance improves health and saves lives by being the difference in whether or not people receive lifesaving medical care.

But perhaps we should focus on another question – not just asking whether people with insurance are more likely to receive medical care but asking where they receive it. According to a study in the Annals of Internal Medicine, increased insurance coverage under Obamacare made it easier for people with emergent medical problems to go to a hospital close to their homes, saving them travel time that might have been the difference between life and death.

When people are emergently ill, time is precious. Every minute a heart attack goes untreated means the death of more heart muscle; every delay in stroke treatment leads to the demise of more brain tissue. It matters whether people arrive in the ER in 15 minutes or 50. Insurance coverage reduces the time it takes for people to receive emergency care because they go to ERs closer to home.

You see, nearly two-thirds of uninsured people with urgent medical needs drive to the hospital when they are sick rather than call 911. They arrive by car to avoid ambulance costs, or because they don’t realize their symptoms are from an urgent problem, or because they want to go to what they perceive to be a lower-cost hospital.

Congressman Labrador was correct that hospitals are required to provide emergency treatment to patients regardless of their ability to pay. But the law does not require hospitals to provide that care for free. After hospitals provide emergency care, they bill patients, leaving some uninsured patients with crippling debt. Some hospitals are known to be more forgiving of such bills than others, or simply charge patients less for such services, which gives uninsured patients an enormous financial incentive to drive to those hospitals even when other hospitals are closer by.

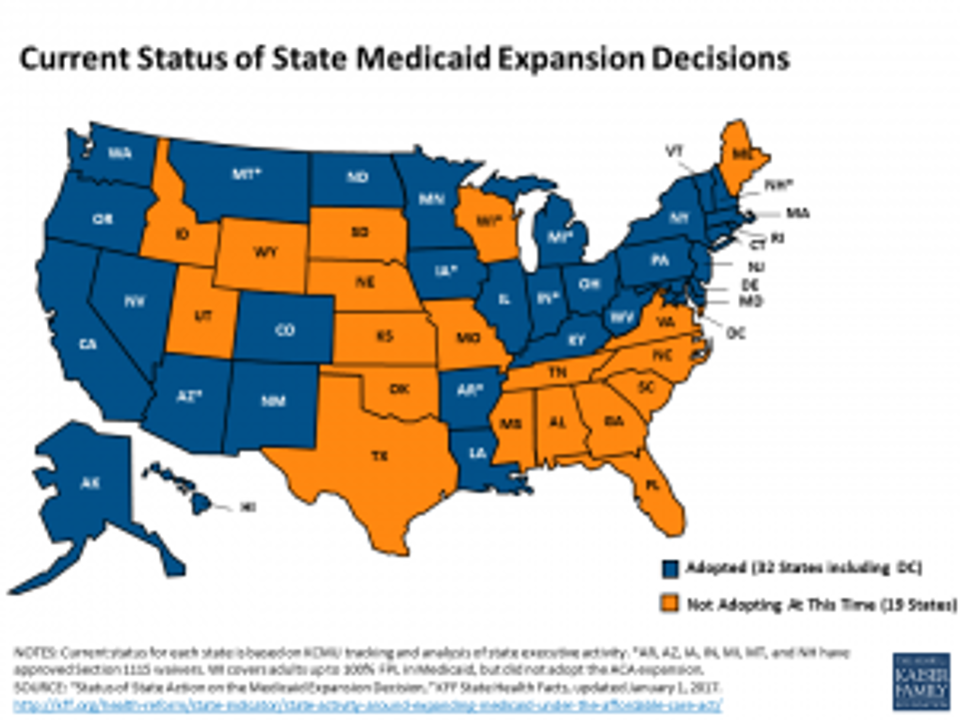

As a result, people without insurance drive longer distances for emergency care. How do we know this to be true? Researchers looked at ER use in states that expanded Medicaid coverage under Obamacare compared with ones that didn’t. Here’s a picture of the states that did and did not expand Medicaid:

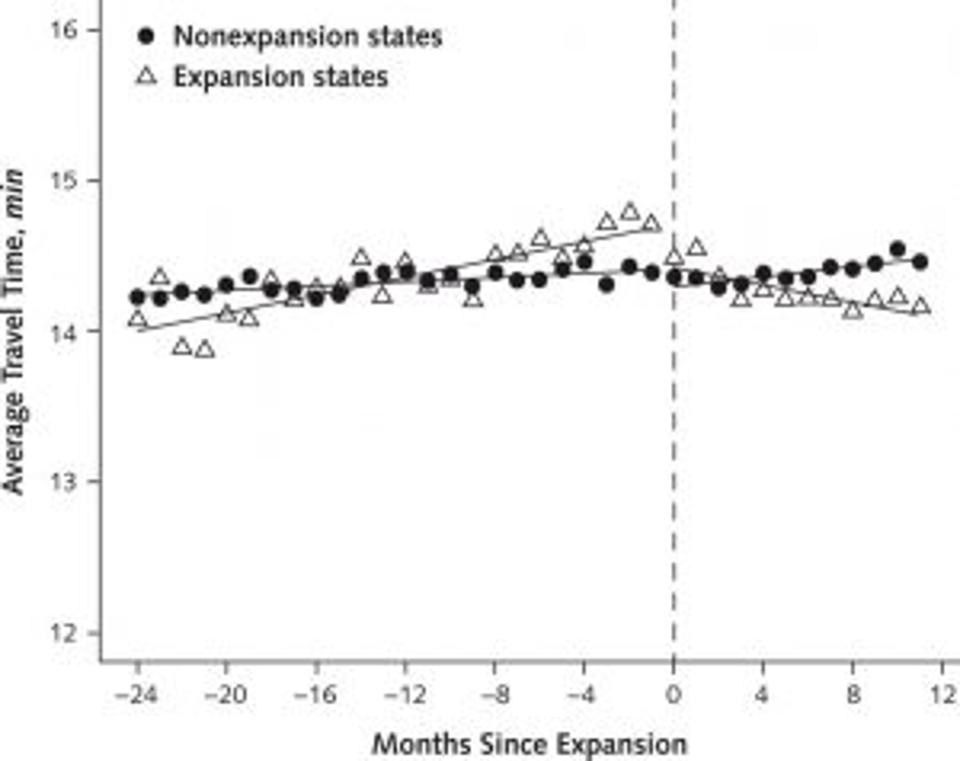

The researchers, led by Craig Garthwaite from Northwestern University, looked at travel distance for ER use in expansion versus non-expansion states. They homed in on nondiscretionary visits – truly emergent medical needs. In other words, they didn’t look at people with a runny noses.

They discovered that travel time was reduced in the Obamacare expansion states but not in states that refused to expand Medicaid:

Importantly, this study doesn’t prove that Medicaid expansion saved people’s lives by reducing the time it took for them to get to the ER. Measuring the impact of insurance on life expectancy is a very tall scientific order. The primary thing health insurance does is protect people from the financial consequences of illness and help hospitals and providers get paid for their services.

Nevertheless, the time-to-emergent-care study was large and rigorous, and the findings are not subtle. And the connection between time to treatment and treatment outcomes is well established for many emergent illnesses. It would be surprising if no one, anywhere, was harmed by travel-related delays in receiving emergent care.

Which makes the bottom line clear. When people are emergently ill, they need medical care ASAP. Time spent driving to distant hospitals because of financial concerns is time for illness to advance. Someone needs to tell Congressman Labrador – and other legislators who are dubious about the benefits of healthcare insurance – that programs like Medicaid benefit their constituents by enabling them to get emergent medical care quickly enough to save their lives.

The above material was prepared by Forbes.